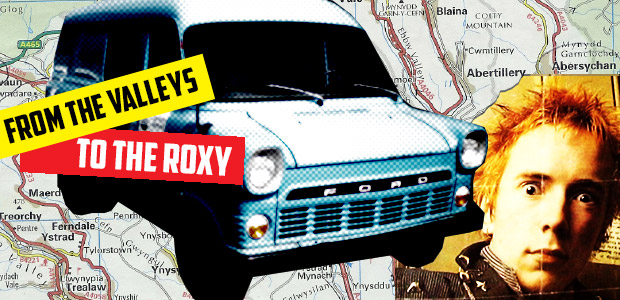

Here’s the story of how the punk revolution changed everything for this Welsh boy living in Cardiff in the 1970s, and how the dreams of rock’n’roll stardom took a blow when faced with the grim reality of a night at the infamous Roxy Club in London.

Cardiff, mid 1970s: Exercise books and school lunchtime dreams

London. The Big Smoke.

Where popstars roam the streets and the famous and infamous collide in an exhilarating crash of fashion, youth and, most of all, energy. Or at least that’s how it appeared to a 15 year old aspiring rock drummer living in the less than fashionable suburbs of Cardiff.

I can remember school lunch hours feverishly pouring over the latest Melody Maker music weekly, eyes enviously gazing down at the huge lists of bands compiled under “London, W1.”

I’d look longingly at the exotic sounding clubs – the 100 Club (where the Rolling Stones played), the famous Speakeasy (where all the stars hung out), and, of course, the legendary Marquee where Jimi Hendrix and Led Zeppelin had played!

Somehow, my hometown’s offering of Racing Cars at the Cardiff Top Rank’s “Implosion” night and the heavy riffage of Lone Star at the “New Moon Club” just didn’t seem as enticing.

It was so rare to find any good bands playing in town that sometimes we travelled up deep into the dark Welsh valleys for rare one-offs by hotly tipped London bands, who clearly hadn’t realised what they’d let themselves in for.

For most bands, the experience of one night at the Tonypandy Royal Naval Club was enough to deter them from ever crossing the Welsh border again – and that’s if they hadn’t already got lost trying to find a naval club located nowhere near the sea.

1975

Supertramp and Fenders

It was 1975 and I was heading down to the big city lights with a school friend who’d saved up to buy a guitar.

Not any old guitar either- he’d come to London to buy a Fender Stratocaster, the very same guitar that Pete Townshend played!

It was already dark by the time we reached Paddington, my friend buttoned up against the winter’s chill in his fashionable army surplus greatcoat, while I was resplendent in my all-denim outfit, complete with defiant cannabis badge socking it to The Man.

Thirty minutes later we were at Tottenham Court Road station, our platform boots forming an uneasy alliance with the icy pavement as we tottered off towards the famous Tin Pan Alley – the street where the stars bought their equipment!

Of course he didn’t buy the guitar. He didn’t have enough money in the end and reluctantly decided to come back in a few weeks that turned into years.

It wasn’t a complete write off though as we did manage to find the exact spot where David Bowie posed for the back of the Ziggy Stardust album.

And we walked past the Marquee (then in Wardour Street) swearing blind that we’d be headlining there one day.

Valley life

Cabaret and chicken-in-the-basket in Cwmamman

From the age of 15 onwards, I’d been mostly drumming in vaguely likeable rock ‘covers’ bands, mainly playing Cardiff pubs and clubs, with the occasional terrifying trip up to the Working Men’s Clubs of the Rhondda and Rhymney Valleys.

Here was a different world where you soon learnt the value of playing whatever songs were asked of you – no matter how awful – or face a sea of flying cans and offers of fights.

My, my, my…

In the smoky back rooms of the Valleys, the hard drinking audiences weren’t interested in hearing anything new – so long as you could put together a passable set of well known songs, you’d be fine.

We pushed the rock envelope as far as we could in the environment with reasonable approximations of hits by the Stones, Who, Quo etc., but woe betide any band who dared challenge the crowd with the dancefloor clearing words, “Here’s one of our own songs we’ve written.”

As the night wore on, it was not unusual for a drunk old miner to stagger onstage mid-set and insist that you let him sing ‘Delilah’ or some other Tom Jones classic, with his mates in the crowd enthusiastically applauding the idea.

Refusal in this situation was not an option as the crowd would instantly turn on you, so many’s the time we’d gamely strum along to Tom while some bloke clutching a fag and a tumbler of Watneys Red Barrel would murder the song.

Even if you managed to avoid any wannabe Tom Jones and the bottles weren’t heading your way, there was always the prospect of the the soul-destroying ‘pay-off.’

This is where a member of the committee would walk onstage mid-set to the cheers of the crowd to pay you a percentage of your fee to get you off the stage.

Although I never suffered this fate, it must have psychologically damaged musicians for years.

Punk arrives, record collection gets changed

1977. School was out and punk was in full swing.

I can remember hearing “God Save The Queen” for the first time and wondering why I had ever bought an Eagles album.

Here was something real. This meant something. They were angry, I was angry too, and what’s more my mum hated them.

As soon as I’d seen Johnny Rotten’s sneering face outraging the tabloids, I knew that I could no longer get my kicks out of drumming along to the bloody Doobie Brothers.

I’d half heartedly cut off my long Bolan-esque mane and had ended up with a hideous compromise that looked like a cross between a failed 1960’s footballer and Mick, the presenter from ‘Magpie’. But not as good looking.

I’d been one of the first to walk through Cardiff Queen Street with shiny punky PVC trousers and ripped clothes, regularly running the gauntlet of taunts and violence from the nine button disco smoothies and wannabe Welsh Hells Angels, and it felt good. Suddenly people were taking notice.

The NME and Sounds became my bible.

My world started to revolve around London, where it seemed the eyes of the world were looking on as punk started to rip up the nation’s youth.

Even better, it seemed that just so long as you could put together a few songs and look the part, you could join in too. And I wanted to be there.

Freed by punk

I joined a band called Beggar from the Valleys who seemed to possess all the right ingredients of a good punk band – modest musical prowess, a pile of attitude, some hummable choruses and a suitably aggressive 100 mph approach to every song.

The truth was that we were really a fast R’n’B band – more Dr Feelgood than Damned – but our sound was aggressive enough to pass for punk with a deft re-jigging of the lyrics.

I think our twelve song set used to come in at around 20 minutes, each one belted out at maximum speed – apart from of course, the obligatory heavy-handed, mid-set attempt at white boy reggae.

We started out with a couple small pub gigs around Cardiff where punk was just starting to take a hold and the crowds did their best to reproduce an authentic ‘punk’ environment.

Spotty youths pogoed to our basic, but insistent repertoire, while the singer did his best to avoid the snowstorm of stage-bound phlegm.

As a drummer, I soon learnt the advantages of setting up my kit as far back as possible and tilting my cymbals to form a useful mucus shield.

Gigs up the valleys were always a little bit special, with rival gangs facing each other across the dancefloor before the inevitable feast o’fisticuffs broke out.

Occasionally, our singer – never one to turn down the offer of a scrap – would leap into the brawl mid-song, mic still in hand, adding an impromptu soundtrack of “oofs” and ows” over the band’s backing track.

To the Roxy!

And then we finally managed to blag a gig at the famous Roxy Club in the heart of London. The Roxy!

Where the Clash had played! Where X Ray Spex and the Lurkers and the Cortinas and The Banshees and the rest of them had performed. And we were going to play on the same stage!

We picked up our equipment from the disused garage in the Valleys that served as a rehearsal studio and set off for the bright lights.

Someone had brought along some lighter fluid and we all tried to sniff it during the long journey down like real punk rockers. The van smelt awful and we all had thumping headaches by the time we arrived in London.

Still we were here and this was it! The Roxy! London!

Look out London!

We bundled out of the van, sneering, leering and trying to look tough at baffled passers by, before walking up to the club, trying hard to conceal our obvious excitement.

Stuck outside was a poster advertising forthcoming gigs and our initial enthusiasm was dampened somewhat by the discovery that we’d been booked into ‘Gay Night at the Roxy’ supporting a band ominously called Handbag.

The sound of an extremely camp singer echoing up the dark stairs added to our suburban discomfort – back in the 70s homophobia was rampant, even though millions tuned into Larry Grayson every week, and the sexually ambiguous David Bowie was topping the charts.

In the shared dressing room backstage, the bass player confided that he was slightly worried about changing as – and apparently this is common amongst the bass playing fraternity – he wore no underpants. Further research in my later bands revealed that 50 per cent of bass players do indeed forgo underwear.

Ble mae scenio?

The club looked like it had been squatted for years – there was graffiti everywhere, the toilet doors were hanging off their hinges, and your feet stuck to the floor.

But this was punk and it was all about attitude and we had that by the truckload and playing the Roxy was proof that we really had arrived and were ready to take the scene by storm.

At 9 o’clock, when we strutted onstage ready to show the world what we were made of, we swiftly realised that the scene had in fact been, happened and moved far, far away.

To an audience of seven men and the club owner’s dog, our songs fell silently into the dark chasm between the stage and the minimal crowd. Even the dog remained asleep in front of the speakers.

During the gig, the singer ran to the edge of the stage only to find it was merely a piece of drink-hardened carpet jutting outwards. The carpet snapped and sent him stumbling onto the empty dancefloor, his amplified “oof!” causing some amusement in the shadows. The dog growled.

After twenty minutes of unappreciated social sloganeering we left the stage to the same total silence that had greeted our arrival.

“Perhaps there was an A&R man out there”, optimistically offered the bass player backstage, cautiously changing his trousers behind his guitar case.

The three members of Handbag looked at us in amusement.

We packed up our gear in silence, loaded up the van and went back to the club for payment. “Quiet night tonight, lads” offered the disinterested promoter, handing us three pounds fifty in loose change.

We headed back to the Welsh valleys in the early hours, over thirty quid down on the venture and facing a long and uncomfortable journey home.

“Can’t wait for the next London gig,” muttered the singer above the noise of the rattling van.

“Hell, yes!” we all agreed.

Mod movement

A few weeks later we all moved in to a grim flat in Leyton, East London, and became regulars at the Bridgehouse in nearby Canning Town.

The venue became the focus of a mod revival, and Beggar’s R’n’B driven pop sound proved a perfect fit, and we became part of a growing scene. It was exciting times. and we ended up being featured on the influential ‘Mods Mayday 79‘ album. I’ll write more about that another time, if there’s enough interest!

Update: April 2020

An unexpectedly revival of interest in 2011 saw a collection of our demos being released in a CD album release. Record Collector magazine were very kind in their review, concluding,

This set features two studio demos – 16 tracks in all – recorded in 1978 and ’79. It reveals a band that, if blessed with the breaks and decent production, could have gone all the way.

Note: A shortened version of this article was originally published on urban75.com, and an extract was reproduced in the book, ‘The Roxy London WC2: A Punk History‘.