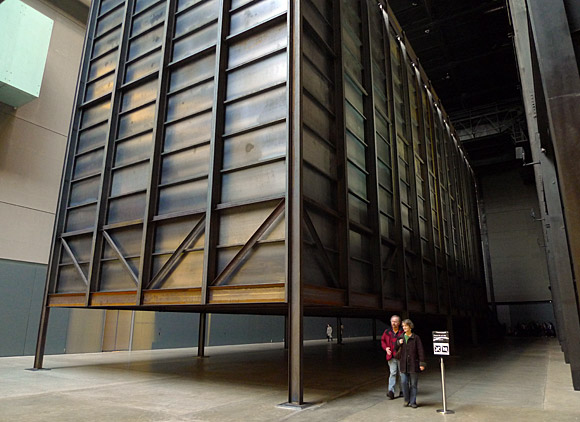

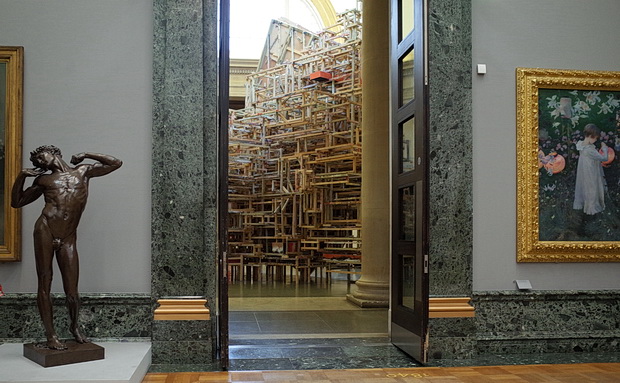

This year’s Tate Britain Commission is a real feast for the eyes, with Phyllida Barlow’s massive ramshackle wooden constructions almost filling every inch of the gallery’s voluminous Duveen Sculpture Court.

Entitled Dock, the piece is dominated by five battered containers, suspended on what looks like a particularly precarious assemblage of wood scaffolding, straps and braces.

Like a supersized child’s balsa wood fantasy, the work dwarfs those walking under it, with its crazy selection of bolted on joints and criss-crossed beams making it almost impossible to work out what is supporting what.

Walking through the hall, you come across a tall column that looks like its made of a giant battered piece of cardboard, held together with brightly coloured electrical tape.

An almighty pile of wooden pallets supporting a half-toppled array of roughly painted sheets of thin wood follows.

At times it looks like the aftermath of an explosion in a furniture factory, with pieces of wood hammered on at random angles, while the huge suspended tube looks likes it’s ready to be used in a mediaeval siege.

I loved the work. It was unexpected, fun and chaotic and I think I enjoyed it almost as much as Adrian Searle at the Guardian:

What an exhilarating work this is. Gothic, slapstick, over-reaching, trammelling, dock presents the world as theatre set, a gigantic child’s play of sculptural ambition, an anti-monumental act of deconstruction, a huge bricolage.

It is also a wonderful parody of sculpture’s history of self-regarding masculinity, all that conspicuous labour and heft and muscle-flexing strain. Dock is a summation of Barlow’s work to date. There’s a word for this: Wow.

Once my senses had sufficiently recovered, I took time to explore some of the British collection, soaking up some of my favourite works of art, including John William Waterhouse’s The Lady of Shalott from 1888 (below).

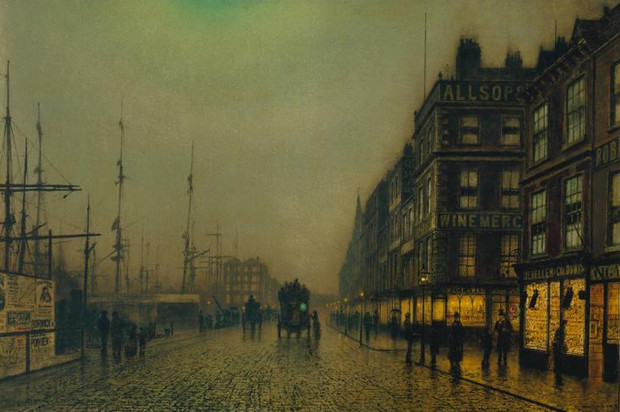

His work isn’t particularly fashionable, but I’m always drawn to the industrial noir of Atkinson Grimshaw (below), with Liverpool Quay by Moonlight from 1887 being a painting soaked in winter mist, glistening gas lamps and atmosphere.

I couldn’t afford the hefty £14.50 to view the British Folk Art exhibition, so instead immersed myself in the books that accompanied the exhibition, and saw some fantastic work.

If you’ve the cash to spare, I’d suggest that it’s well worth a visit – otherwise head for the bookstore!

Students show off their work inside the gallery – various projects were being held the day I was there.

A look up at the impressive dome of the 1897 gallery.

More: Tate Britain site