London placard carriers and 'sandwich men', 1820 -1840

Sketches by George Scharf. Article by u75 editor, Sept 2004

(Content ©urban75, 31st January 2010)

Much like today, London was plastered with advertising, with armies of chalkers and 'external paper hangers' decorating blank walls, empty shops and wooden hoardings with advertisements.

The combined inconveniences of an advertising tax and increased competition for poster space led advertisers to a simple conclusion - make the messages become mobile!

Described by the writer William Weir as 'peripatetic placards', Prince Pückler-Muskae gives an interesting account of how the technique was employed in the 1820s:

"Formerly people were content to paste them up; now they are ambulant. One man had a pasteboard hat, three times as high as other hats, on which is written in great letters, 'Boots at twelve shillings a pair - warranted'.

Another carried a sort of banner on which is represented a washerwoman and the inscription, 'Only three-pence a shirt'."

Looking like a fancy dress version of today's human billboards, placard holders were initially dressed in outlandish, eye catching clothes with banners taking on a multitude of shapes.

Later illustrations portray many street advertisers as being down at heel and shabby (which would hardly enhance the appeal of the the advertiser's product).

Along with the 'standard bearers' there were also what Weir described as 'a heraldic anomaly, with placards hanging down before and behind like a herald's tabard'.

In case you've no idea what he's on about, Dickens described the sight more eloquently: 'a piece of human flesh between two slices of paste board'.

And hence the 'sandwich man' was born.

In the 1828 sketch above, you can see an early example of a sandwich man advertising the Battles of the French Army at the Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly.

This drawing by Scharf shows placards advertising the results of two elections at Westminster and the City and an exhibition of the Society of British Artists, Suffolk Street (1818-1824).

The large billboard facing the artist advertises 'Belzoni's Exhibition at the Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly'. Giovanni Battista Belzoni was a 6ft 6in Italian strongman who became fascinated with Egyptian antiquities after a failed business trip to Egypt.

Belzoni shipped over a huge collection of artifacts to England in 1820, and the exhibition opened in May, 1821.

Running for a year, the exhibition created a sensation and sparked off great public interest in Egyptology.

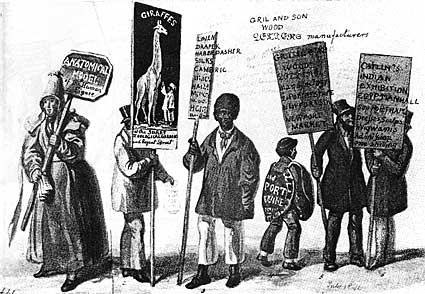

A selection of billboards from the 1830s. Note the curious 'mock turtle' sandwich board advertising port wine.

From left to right, the billboards read, 'Anatomical Model of the Human Figure', 'Giraffes at the Surrey Zoological Gardens at Regent Street', 'Linen, Haberdasher, Silks, Cambric...', 'Port Wine', 'Gril and Son, Wood Letters Manufacturers, Newport Market and 'Catlin's Indian Exhibition Hall - 500 portraits, drapes, scalps, wigwams. Admission One Shilling'.

The novelty of placard carriers soon worn off, so advertisers were pressed to come up with new attention-grabbing ideas.

In 1826, the owners of the Weekly Chronicle decided that the simple process of multiplication would do the trick, and dispatched a mobile band followed by a legion of board carriers onto the streets of London.

The shuffling horde advertised a free gift of a print of the famous Nassau Balloon.

In their never-ending quest to capture the eye of passers-by, bigger and more bizarre displays were always being dreamt up.

Robert Warren of 30 Strand was particularly adventurous, coming up with a novel walking display of blacking tins (1830s).

In the drawing above, Scharf recorded a row of six blacking tins walking along The Strand, which must have made for an interesting sight.

The large procession of trumpet-parping placard-carriers (1834) to the right bear the message, 'All The Alamanacs are given away with Bells Weekly Messenger'.

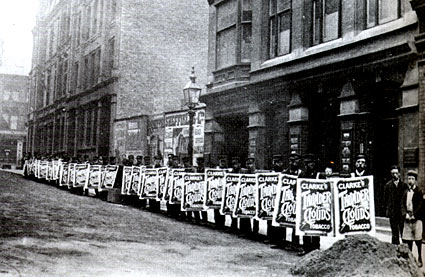

Some thirty-odd sandwichboard men ready to parade around Birmingham advertising, 'Clarke's Thunder Clouds Tobacco.'

Later developments saw horse-drawn advertising displays being driven around the streets of London.

Prince Pückler-Muskau describes how "Chests like Noah's Ark, entirely pasted over with bills, of the dimensions of a small house, drawn by men and horses, slowly parade the streets, and carry more lies upon them than Münchausen ever invented."

There were drawbacks to this new innovation: the advertiser's innate tendency to make everything as big as possible meant that the messages were nigh-on impossible to read. According to Punch, "They are now on so gigantic a scale, no ordinary vision can take in more than half a letter at a time".

Moreover, the carts didn't go down with the public, creating increased congestion and providing a hazard to pedestrians.

As Punch put it, "Go where you will, you are stopped by a monster cart running over with advertisements, or are nearly knocked down by an advertising house put on wheels, which calls upon you, when too late, not to forget 'Number One'"

The continuing public outcry against advertising carts eventually resulted in them being effectively suppressed by the London Hackney Carriage Act of 1853.

Sources:

George Scharf's London, Sketches and Watercolours of a Changing City, 1820-1850 (Peter Jackson)

Advertising in Britain, A history (T R Nevett)

More info:

London human billboard photo collection

|